Achieving Eudaimonia With Aristotle: How to Live a Fulfilling Life

As philosophers in training, or even as regular citizens roaming our graying, anonymous streets, it is quite frequent that one turns and asks ourselves from time to time: “What is the meaning of my life?” And, pleasantly enough, this society seems to dearly avoid such an answer. Busying ourselves with overriding media, with work, with play, with distraction—with anything that one thinks will ultimately make us happy, many humans are stripped from the opportunity to reflect. The underlying agreement society shares as one suffocates true desires for prosperity, is that one day, we will find joy, and be happy. However, turning to the roots of thought, acknowledge that many philosophers are disapproving of such ends, such theories. That happiness is not so shallow as money or looks, but rather that true happiness comes from a place of reflection and justice. Of pain and sacrifice. To Aristotle, one of the greatest thinkers of all time; “Happiness is the meaning and the purpose of life, the whole aim, and end of human existence.” Alas, to achieve happiness then, is to first and also achieve Eudaimonia.

Born in 384 BCE, Aristotle's virtuous life was not one of ease. Orphaned at the age of 10, Aristotle voyaged to the glorious Athens, Greece to study in Plato’s Academy at 17. Being associated with Plato until his death, Aristotle continued his studies on the coastal island of Lesbos before returning to Greece to stand as a prime figure in the education of Alexander the Great. Opening the Peripatetics School, Aristotle was known for innovating and teaching in all aspects, holding the manuscript of the Great Library of Antiquity, before retiring in 323 BC from a somewhat anti-Macedonian sentiment. While closely related to Plato, Aristotle's work differentiated in the technique and practical aspects. While Plato's theories radiated theoretical thought, a prose of silver, Aristotle's works were a flowing river of gold. To breach Plato’s sense of idealism, Aristotle seemed to ground his thoughts and perspectives on sense and reality, demonstrating more thorough examinations that challenged Plato to point towards the ground. With many challenges to Plato's metaphysics and morality, one of the most prominent challenged aspects is his concepts of life. Particularly, how to achieve happiness and the ultimate meaning of human existence.

To ask you, reader, what you do or what you hold valuable in your life as an end goal, one might list a multitude of things. Perhaps, it is making money, financial security, or consumption. Perhaps, it is your friends, your family. Nutrition, exercise, fulfillment in education, etc. There are therefore many different goods that humans strive for; apparent “ends” we are set on achieving. However, Aristotle argues that these ends are simply not sufficient in explaining the complexities of human existence. That it is not the socially-constructed material wealth, nor is it the social perception of honor, and not even is it satisfying bodily pleasures of staying alive, which he thinks may be a sufficient life for “cattle”, that should hold the highest good. Rather, what Aristotle thinks differentiates human beings from other forms of life, is our rationality: homo sapiens have the ability to strive for more, to learn to fulfill our highest potential, maximizing our faculties as humans in fulfilling our Telos.

Another aspect of this differentiation, if the first explanation is not bought, stems from Aristotle's Theory of Causation, which explains that everything in life has a Telos: an inherent purpose and a reason for why it is the way it is. For instance, the Telos of a seed is to germinate, grow and eventually reproduce, while the Telos of a caterpillar is to fulfill its bodily needs in order to develop, to metamorphosize into a butterfly, reproduce and contribute to the ecosystem.

This fixed essence in nature, accompanied by the Natural Law Theory, states that nature provides beings the tools to also know what's good and bad, therefore saying that all things in existence are good to the extent that it fulfills their inherent function, and probably bad otherwise. The way humans differentiate in Telos from other beings, however, is again our rationality. Not only must we fulfill our bodily needs, to stay alive and well, but our increased gift in the ability to think, to feel, to judge, and to act upon these thoughts, means our Telos goes beyond the surface, as to have the responsibility of compensation and learning. It is our responsibility in life, to fulfill our extenuating purpose; to be virtuous.

Aristotle’s Character Virtues

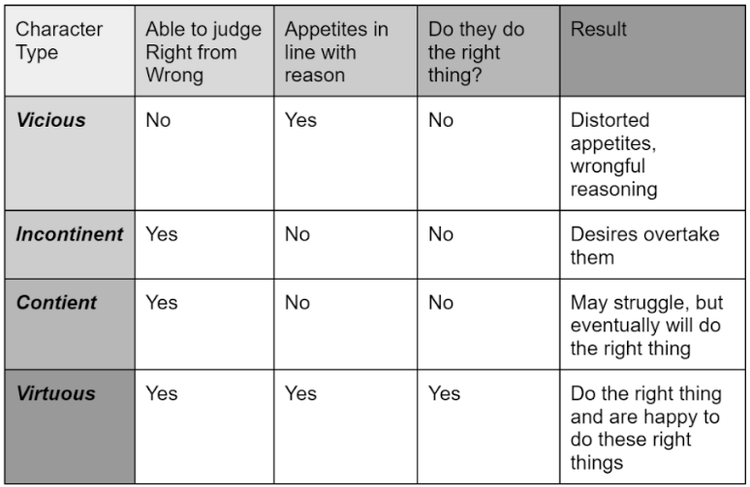

So, in the way that Aristotle deems the highest, most valuable human good as fulfilling our unique Telos of learning and virtue, how does this make us happy? The principal here is not to focus on the different ends of good, but rather that virtue is the end and the highest human good within itself. In the aspect of learning, Aristotle acknowledges two parts of this good: one of practical knowledge and intellectual virtues, which are known, and one of implementation and character, which are experienced. The possession of such virtues however cannot lead to virtue itself. Rather it is the practice of these character virtues that can truly make people good at being a person. And according to Aristotle, being good at being a person means you will be a good person.

Thus, if one can achieve the essence of being a good person, they can achieve Eudaimonia—the highest human good of flourishing and wellbeing—and thus achieve happiness.

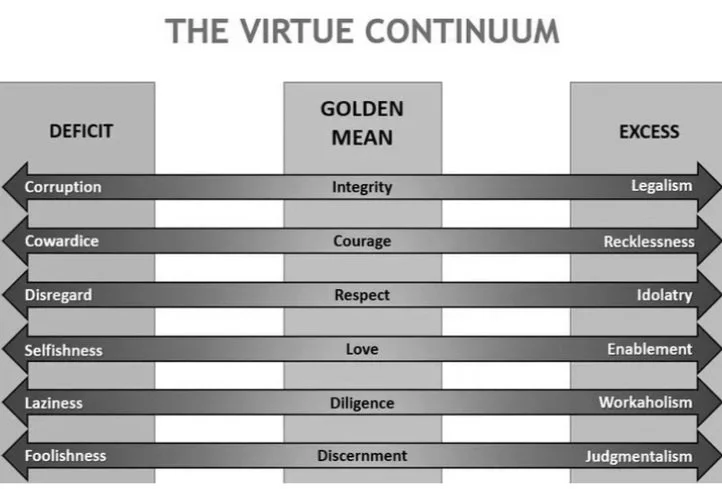

There are many logical ties to clear up. Let's firstly consider the topic of virtue, and return to the idea of Natural Law Theory; knowing when something is good or bad. The Virtue Theory approach to a good life by Aristotle and others does not follow a distinct set of steps or of criteria. Rather, it is a set of character traits that sit in the middle of two conflicting vices; traits such as courage, generosity, temperance, ambition, truthfulness, among many others. Aristotle believed such 12 virtues, if fulfilled, will let one ultimately achieve the maximum human good of Eudaimonia. In this, we can reference the Golden Mean or Doctorate of mean, which places virtues as a middle ground between the two extremes of deficiency and excess in traits.

Aristotle’s Balance of Virtue and Vice - Golden Mean

Therefore, to be virtuous is not to be overly generous, or overly friendly, but rather to use our gift of rationality in understanding to what point our virtues are available. It is not virtuous to intervene with a crime when we are not of help; similarly, it is not virtuous to be brutally honest, as it is not to never tell the truth. Aristotle believes that our rationality and the development of virtue in human beings allow one to work towards understanding the true, resonant state of capacity to act, not just principally, but in regard to a situation. The possession and implementation of virtues in daily life based on the understanding of a virtuous man is ultimately the path to fulfilling our purpose and achieving the highest good.

But why does achieving this ‘ultimate highest good’ matter in the context of happiness? Aristotle believed that Eudiamonia and happiness were mutually inclusive; although a “life well lived” includes much more pain, more discomfort than a relaxing, happy life, it is thought that the highest category of man who is the happiest tends to have inclinations that align with virtue. To reach a point where the things we want to do, those that bring us joy, are deemed also the correct moral action, is when we can truly feel the happiest. Virtuosity, above all else, is the best version of oneself that one can be. And this strain, the struggles, and the development ultimately shape the meanings of our lives and our happiness within them.

As we now understand the ethical thinking of Aristotle, we must then contest some issues with the theory of Eudaimonia, of Nicomachean Ethics: firstly, that not everyone can achieve virtue. There are commonly eternal factors that influence the way an individual thinks, one’s principles, virtues, and ability to foster the Golden Mean of virtues. The level of goodness of the state one inhabits, for instance, comes as a great disadvantage to many in the modern day. As individuals are vulnerable to its state in terms of their ability and their nature, impediments to expressing the highest level of virtue can come with a bad state. Being born poor, born to face suppression, born in a corrupt regime; such aspects Aristotle agrees can limit both virtue and the ability to reach happiness.

However, although many things in life are out of our control, there are many things that are in it. No matter what, there is a part of us that has the ability to change the good within us. To strive for development instead of hiding in our corners. To aim to be a virtuous person, to aim to do what is right. This is the unique quality and value of our meaning, and in this, we should strive. Returning to the question of the meaning of life, Aristotle's virtue ethics allows us to understand that the meaning is simply of good; that we must not fret about the ends of our value, but rather, that value stems from who we are in and of itself. To achieve Eudaimonia is to hold ourselves accountable for fulfilling our moral potential and our human potential. And thus, we shall not turn to the judgment of anyone else, because truly, as Aristotle once said, “Happiness depends upon ourselves”.

Sources:

https://ethics.org.au/ethics-explainer-eudaimonia/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/eudaimonia